By Lauren Valdez and Adriana Valencia

A Fulbright scholarship lets you explore almost anything you want in any part of the world. Through the Fulbright US Student Program, Americans can apply to do research, creative arts projects, obtain a graduate degree abroad, or teach English in more than 140 countries.

With so many options, it can be difficult to pick a country. There are many factors to consider when determining which country and award to apply for. Some countries are more competitive than others. Some countries offer many more awards than others. Some countries have restrictions for what topics can be studied.

After being selected for four Fulbrights between the two of us and coaching people on applications for more than a decade, we’ve learned that the crucial component of any Fulbright U.S. Student application is picking the right country and right award/topic for you. What you need to do is find the combination of these factors that work for you. You need to have a clear link between who you are, where you are proposing to go, and what you are proposing to do.

So where do you start?

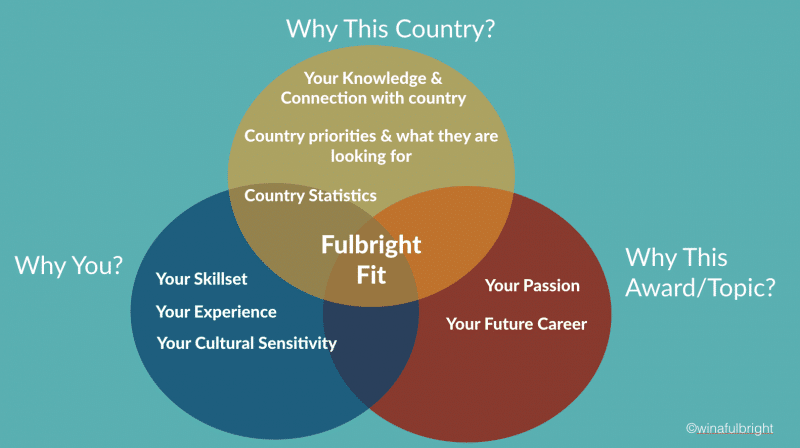

Every strong Fulbright application successfully answers these 3 questions.

#1 Why this Country?

You might want to go to a country you have a connection to, have traveled in, or you might want to go to a country you have never been. Here are some things to consider:

Where have you traveled to or have connection with?

Answers to this particular question can lead you down a couple of different pathways: on the one hand, a close connection with a particular country could give you a compelling reason for choosing that country. On the other: if you’ve spent more than six months in the country to which you’d like to apply outside of undergrad studying abroad, you should potentially considering selecting a neighboring or analogous country, as having spent too much time in-country could potentially make you “non-preferred.” That being said: your choice of country is a deeply personal one; it’s possible to be selected for a country which you’re a heritage grantee (having family origins and personal ties to that country), and it’s also possible to be selected without having been somewhere previously at all.

What languages do you speak?

Some countries have language requirements and others allow English as the primary project language. If you have beginner language skills, especially in common second languages like French and Spanish, keep in mind you will be competing against applicants with advanced language skills. However, if you are a beginner in a less-commonly-taught language, that proficiency can be a huge plus. There are also many countries where you can pursue a Fulbright award in English, so consider these if you have other compelling reasons to be in those countries.

What current events are you following that you are interested in?

These can be at the core of a great Fulbright project. Centering a proposal on current or emerging events and societal trends—and that indicates how you’ll analyze, study, or otherwise document those events—can be a way to support the importance of your project for this application cycle. Awareness of current events and connecting them to effects that they have upon your field of interest or specialization, whether that field is public health, the arts, or public transit funding, can ultimately strengthen your application and make it timely.

One caveat: political unrest or instability can be reasons to avoid proposing certain countries. It’s rare but not unheard-of for programs in countries to be cancelled if the Department of State determines that there are security concerns significant enough to do so.

What are the country priorities?

Fulbright Host countries may have specific preferences; these are listed in the country profile summaries. Sometimes they prefer STEM projects, or PhD students, or for grantees to be in specific regions or cities of the country. Review the country summaries closely and try to best align with the host country’s interests. You want to make sure you fit the country requirements. The more competitive a country is, the more closely you want to align with its priorities.

It’s also important to understand whether or not your proposed project is a good fit for your proposed host country. Politically sensitive topics, and work with vulnerable populations such as refugees or children, are subject to extra scrutiny; not all subject matters are appropriate for all Fulbright proposals and host countries. Some countries may not allow proposals that hint even vaguely of government criticism. If you are unsure what your country of interest prefers, you can review project titles for the past few years in the grantee directory and see what fields the country often selects. You want to make sure what you are proposing is relevant to the host country.

How many applicants will I likely be up against?

Know the country criteria and applicant selection statistics. You want to lead with picking a country you are passionate about, where you can do the work you want to do, but knowing the country statistics can help you narrow down if you are trying to choose between a few countries.

No matter your level of experience in or with the country, you need to clearly demonstrate in your application why you want to do a Fulbright in that country and your interest in the topic: while you don’t need a specific background in that topic, you need to demonstrate preparation to undertake your proposed project.

It will be obvious if you haven’t done your homework on the country and are only applying because of a relatively high acceptance rate. Don’t just talk about things someone visiting the country on a two-day bus tour would know. You may want to mention policies, key historical moments, social or cultural movements relevant to your proposal, and/or your cultural interests. Spend time reading about the history, culture and politics of the country.

#2 Why this Award/Topic?

Find a topic that makes you tick. You want something that puts a figurative spring in your step. Choosing something in which you’re genuinely interested makes not only a stronger application, but can lead to a successful, individually satisfying Fulbright experience that can positively affect your career path, and your life trajectory generally.

If you are not ecstatic about teaching English or are doing something because of a parent’s expectations, it will be challenging to craft a compelling proposal. A Fulbright is a unique opportunity to explore whatever you want for 8-10 months. Think deeply about your passions, your interests, and your post-Fulbright future.

You can think about it as finding the country and topic that best connects your past experiences to what you want to do in the future. For example, maybe you studied abroad in Spain, learned Spanish and want to have a future career teaching English as a Second Language (ESL) in the U.S. A Fulbright English Teaching Assistantship in either Spain or another Spanish-speaking country would be a good stepping stone to that future career path. The exact choice of country could depend on your interests, ETA availability, and whether or not your connection to Spain made you want to return, or if you are interested in exploring a theme you may have considered in Spain or another country, for example.

Here are a few questions to consider:

- What fields interest you (public health, history, etc)?

- What do you see yourself doing 2 years from now? 5 years from now? How would a Fulbright help build your experience to get there?

- What class or topic in school were you really excited about? Could you continue to explore that topic or theme on a Fulbright?

- If you could spend 8-10 months doing anything exploring something first-hand, what would that be?

#3 Why You?

A successful application really stems from who you are, your experiences, interests, passions, and future path. You can think of the Fulbright as a stepping stone connecting you from where you’ve been to where you want to go. Everything from your experience and language skills to your affiliation and chosen methods must show that you are capable of doing what you propose.

Here are some questions you can consider:

- What got you interested in that topic or country?

- What languages do you speak?

- Why do you want to teach English and what would make you a good teacher?

- What experiences have you had that led to this?

- How have you been building your competencies and skills to be prepared to do what you are proposing to do?

- What experiences have you had that show you are culturally sensitive and adaptable?

We call this finding the Fulbright Fit. You need to find the intersection of these 3 questions when it comes to picking the right country and award for you. A Fulbright is an extension of who you are. You can’t copy a sample essay and expect to win. Thousands of people study abroad in Western Europe and want to go back. What makes you stand out? You need to find a combination of your interests, experiences, and skillset that combine with what your proposed host country is looking for.

When you have a proposal that aligns these three components—host country, award type and project, and the special sauce that makes you you—you have the beginnings of a strong Fulbright proposal. When you submit a proposal that’s truly the best project for you, whether or not you receive the grant becomes secondary: taking the time to articulate your interests and goals and what you can do to attain them is in itself a valuable exercise. Getting the Fulbright then becomes the icing on the cake.

Lauren Valdez and Adriana Valencia met at UC Berkeley and co-founded Win a Fulbright to help more people access the Fulbright U.S. Student Program. Between the two of them, they’ve been selected for four Fulbrights. They’ve also been successful in applying for many other grants, from graduate research funding for themselves to multi-year, multi-million-dollar strategic initiative funding for nonprofits. They’ve also served on selection committees for various scholarships and grants. In short: they understand the grant application process at a deep level. Adriana’s first Fulbright was a Fulbright U.S. Student Program grant to Egypt in 1997 and Lauren’s was a Fulbright U.S. Student grant to Brazil in 2011.

© Victoria Johnson 2019, all rights reserved.